Kira Fröse

German artist transforms mundane materials into tactile installations that challenge the traditional distance between viewer and artwork

NEW YORK – “I need to touch this.” The phrase that titles the artistic manifesto of German sculptor Kira Fröse, born in 1992, captures the essence of work that challenges conventional boundaries between observation and tactile experience. Specializing in sculptures and installations, the artist creates pieces that seduce the eye and provoke an irresistible desire for physical contact, purposefully blurring the boundaries between what is meant only to be contemplated and what begs to be touched.

With a degree in fine arts from AKI ArtEZ Academy in Enschede, Netherlands, where she obtained her bachelor’s degree in sculpture in 2017, Fröse has built an artistic trajectory based on the sensory exploration of materials. Between 2018 and 2022, she established herself in Rotterdam, where she developed her individual practice and collaborated as an assistant to renowned artists, including Anne Wenzel, Maaike Kramer, and Stephan Marienfeld. Her works are currently part of important Dutch collections, such as those of Museum LAM in Lisse, Museum Jan Cunen in Oss, and Stichting Kunst & Historisch Bezit A.S.R. & Aegon.

Photo: Courtesy of Sophie Carree

Education at the Netherlands’ Most Rebellious Academy

The choice of AKI for her education reflects Fröse’s artistic philosophy. The institution, founded in 1946 by textile manufacturers in Enschede, in the east of the Netherlands, transformed over the decades into the art academy with a reputation for being the country’s freest and most rebellious. Originally created as Academie voor Kunst en Industrie to educate textile designers, the school abandoned its traditional role to focus on free modern art.

At AKI, there’s a belief that the gap between thinking, saying, and doing should be as small as possible – a philosophy that aligns perfectly with Fröse’s intensely physical creative process. During the making of her works, she kneads, caresses, strikes, builds, and touches everything with her hands, in a method that reflects the very essence of her work: the impossibility of separating creation from sensory experience.

Photo: Courtesy of Sophie Carree

The academy, which currently is part of the ArtEZ Hogeschool voor de Kunsten group after a 2002 merger, remains small but comprehensive. With workshops for metal, plastics, screen printing, printing, ceramics, and woodworking, the institution offers complete infrastructure focused on individual development. Housed in a former textile factory in the Roombeek district, the steel and concrete structure, with its cast floors and large windows, remains intact, serving as a metaphor for the transformation of industrial spaces into environments of creative exploration.

The combination of disciplines, the international composition of students, and the meeting of innovation, art, and technique in projects with the University of Twente make AKI a special place to study as a creator. Located far from the urban bustle of the Randstad – the densely populated region that includes Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Utrecht – the school offers the atmosphere of concentration that its motto evokes: a Platonic walled garden where it’s possible to hear the outside noise but still focus on work.

Materiality as Discourse

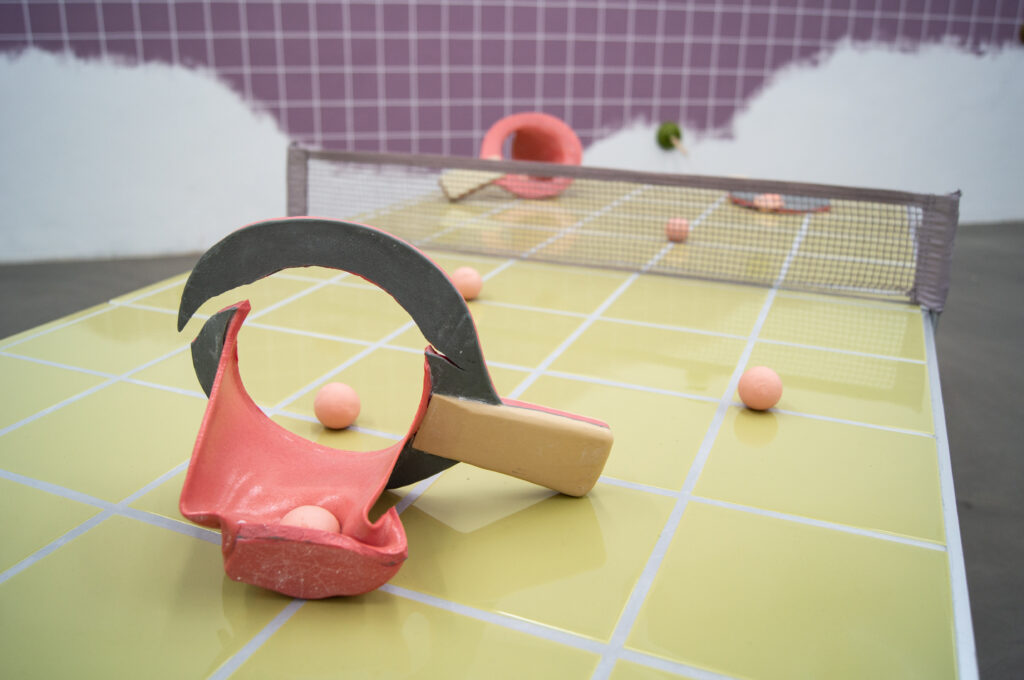

Fröse’s work focuses on materiality and the tensions that emerge from the confrontation between opposites: fluidity versus solidity, movement versus immobility, aesthetics versus imperfection. The artist works primarily with ceramic, plastic, plaster, glass, and textile – materials chosen not only for their visual qualities, but above all for the haptic effect they produce. “All these materials have their own will and come accompanied by a certain stubbornness by their own nature – just like me,” states the sculptor.

Her creations start from elements of everyday reality, but go far beyond simple representation. Fröse produces static objects that suggest movement, pieces that seem light and soft despite the heaviness of the material. Shiny surfaces and structured fluid forms compose a visual vocabulary that, although subconsciously inspired by nature’s aesthetics and everyday objects, transforms into something entirely new and disconcerting.

Photo: Courtesy of Sophie Carree

The technical mastery acquired at AKI, particularly in the ceramics workshops that the institution maintains, allowed Fröse to develop the expertise necessary to manipulate recalcitrant materials and transform them into forms that challenge their natural properties. The academy’s emphasis on doing, on shortening the distance between thought and execution, clearly manifests in her practical and tactile approach.

The Bathroom as a Space of Confrontation

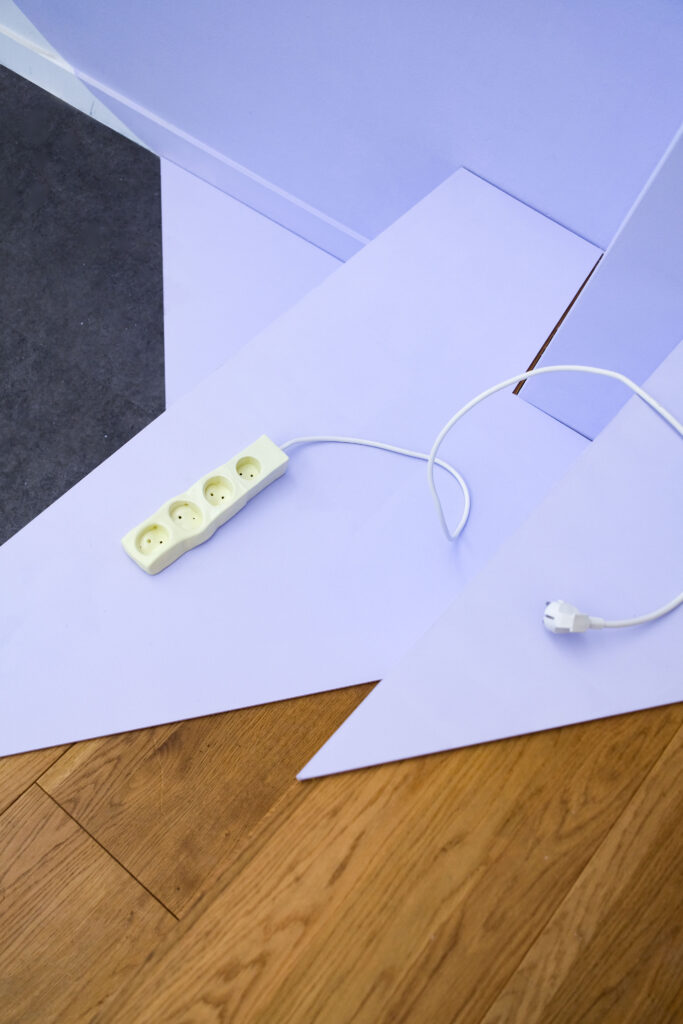

A unique aspect of Fröse’s work is the displacement of the exhibition space to the intimate sphere of the bathroom. As critic Florian Stein observes in a 2021 text, the artist transports the encounter with art to that environment where we’re alone with our bodies, examining our own irregularities. In this private context, the surrounding objects – normally silent observers of intimate habits – gain their own will, moving, freezing, or liquefying.

“The limits of our perception are blurred concepts – we feel with our eyes and see with our hands,” writes Stein. According to the critic, Fröse’s works function as an invitation to distrust one’s own senses and reinterpret the habitual. The artist connects elements that don’t belong together, tears everyday objects from their original context and transforms them into units of meaning with their own stories, always centered on confrontations.

Realism and Accessibility

Although she doesn’t explicitly define herself as a realist – a term she associates more frequently with painting – Fröse acknowledges working with her own reality in an authentic and non-idealized way. “I consider things as they are, observe and record a lot based on experiences that I, or others, collect,” she explains. The artist notes that her worldview, reflected in her works, differs significantly from other people’s reality, generating questions both for her and for the viewer.

Frequently, the objects present in her works are broken or don’t function as they should. This deliberate dysfunction questions concepts of value and utility. “That’s why objects are considered worthless by us. The tension field of value fascinates me and gives me satisfaction to give an old object a new destiny – as a work of art,” states Fröse.

Photo: Courtesy of Sophie Carree

For the sculptor, the direct relationship with the viewer constitutes the most interesting aspect of realistic characteristics in art. Recognition provides access and offers the possibility of approach without requiring prior interpretative effort. “I want my work to attract visually in the first instance. All the layers of content can follow when interest has already been aroused,” she explains.

This approach to accessibility echoes AKI’s own philosophy, where there’s a clear sense of structure, but the academy prefers to have the power of a small-scale institution focused on individual development. The atmosphere described as open, where everyone learns from each other, is reflected in Fröse’s desire to create art that dialogues directly with the public without excessive conceptual barriers.

Between Perfection and Imperfection

A fundamental paradox runs through all of Fröse’s work: the understanding that aesthetics can only endure through the presence of non-aesthetic details. When observing her pieces more closely, the viewer discovers that the apparent perfection of organic forms and polished surfaces coexists with deliberate irregularities, process marks, signs of imperfection.

This coexistence of opposites reflects, according to Stein, a deeper philosophical certainty: that apparently contradictory elements actually constitute each other and would have no existence without one another. The solid is defined in relation to the liquid, movement gains meaning in contrast with immobility, and beauty reveals itself through the controlled presence of imperfection.

Photo: Courtesy of Sophie Carree

Critic Sito Rozema, in a 2025 text, highlights that the figurative visual language employed by Fröse is “quite universal and excludes few people,” a quality the artist considers especially valuable. This accessibility, however, doesn’t mean superficiality – on the contrary, it functions as a gateway to more complex layers of meaning that progressively reveal themselves to the attentive observer.

Legacy of an Experimental Education

Fröse’s trajectory exemplifies the type of artistic development that AKI seeks to promote. The academy is much more than a school; it’s a way of life, as its own institutional materials describe. This sense of community and collective experimentation, combined with the robust technical infrastructure installed in the former textile factory in Enschede, provides the necessary environment for artists to develop distinctive personal languages.

The Fine Art bachelor’s degree that Fröse completed stimulates the creative process and encourages choices that correspond to students’ individual talent and ambitions, offering specializations in Painting and in Total Space & Sculpture. The proximity to the University of Twente, recognized for its technological focus, allows students’ work to have a strong personal component without neglecting the fundamental role of technology.

By transforming materiality into discourse and inviting the viewer to become part of the confrontation between visual perception and tactile desire, Kira Fröse reaffirms a frequently forgotten truth: even when looking in the mirror, not everything is as it seems at first glance. Her education at an institution that promises students “you either hate it – or love it forever” shaped an artist who isn’t afraid to embrace contradictions, celebrate imperfections, and challenge expectations about what art can and should provoke in those who experience it.

Website: www.kira-froese.com

instagram: https://www.instagram.com/kira.froese/